On September 7, Prof. Frank Verboven of KU Leuven wrote an article on Politico arguing in favor of the proposed merger between T-Mobile and Tele2 in the Netherlands. Verboven claims in the article that research he did proves investment rises significantly, while prices will rise modestly. Interestingly, the Politico article declared it was sponsored, but not by whom. After I called this out to Ryan Heath of Politico a notice was added that the sponsor was Deutsche Telekom, since then advertisments by Politico on Twitter have promoted the article.

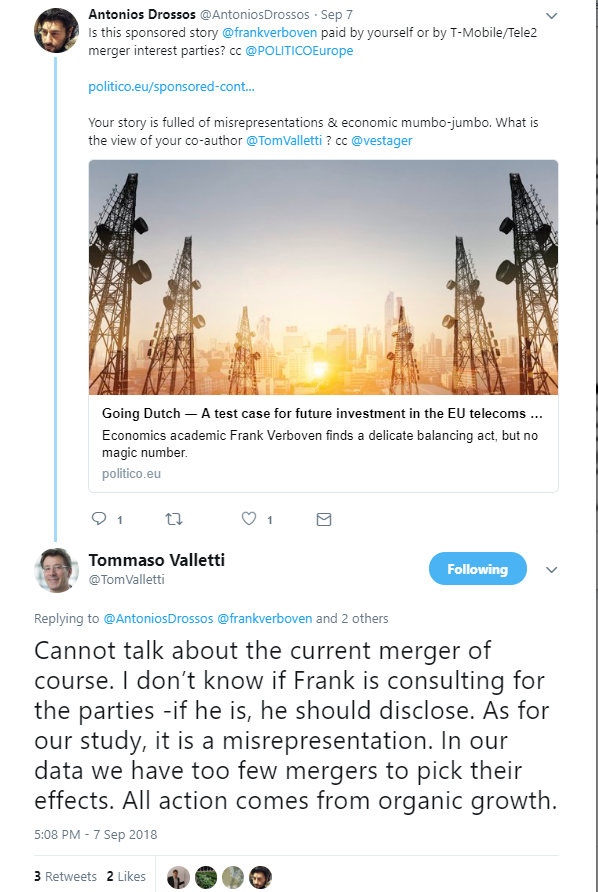

I was alarmed that the article was commissioned by Deutsche Telekom and based itself on research by Christos Genakos (Cambridge) as lead author, with professor Valletti (Imperial College and European Commission) and Prof. Verboven as second and third author for CERRE, a think tank with many telcos, energy companies and some regulators as backers. Valletti is the head economic advisor to Commissioner Vestager. She has to approve or block this merger. That made me suspicious; is the merger a done deal already? However, Valletti commented and denied the article said anything in favor of the merger. In a subsequent tweet he clarified that mergers don’t improve investment but do increase costs for consumers.

So how can it be that Prof. Verboven claims that the same research said mergers benefit investment, when another author says they don’t? Is it just a mistake? Is there a misunderstanding? Is it just hyperbole? Or is there dishonesty at play? I looked around and I saw Verboven gave the same comments to the Belgian newspaper De Tijd on the possible entry of a new operator in Belgium. Here he also cites research he did with Marc Bourreau and Yutec Sun of Telecom ParisTech on the French market. Note: At the OECD I wrote a report on mobile markets with four and three mobile operators and the effects of increasing or decreasing their number.

Verboven uses three arguments:

- Prices for consumers will increase modestly. (citing Genakos)

- Mergers lead to considerable increases in investment, more than the increase in prices and don’t decrease total industry investment (citing Genakos)

- New operators lower the quality of service(s). (citing Bourreau)

I will show that the research does not say this. It says the exact opposite. Prof. Verboven misrepresents the conclusions of the research. Not only do prices increase, revenues increase by hundreds of millions, whereas investment rises by only a hundred million. New networks however increase quality and service offerings. It is impossible that he wasn’t aware that the research doesn’t support his conclusions. It is also not hyperbole or a consultant answering his master’s voice. This is an academic incorrectly citing academic research he (co-)wrote.

Prices for consumers will increase.

Verboven states in the article that: “On the one hand, standard economic analysis suggests that mobile mergers tend to result in some price increases, but the magnitude of these are, on average, modest in light of the general sharply decreasing price trend observed over the past two decades. He then argues that the introduction of Tele2 in the market didn’t lead to lower prices, other than what could’ve already been expected. In addition that Fixed Mobile Convergence puts Tele2 and T-Mobile at a disadvantage and there are the many MVNOs in the Dutch market, that will constrain price increases.

These statements are difficult to square with the observed effects and contradict the report he himself was a co-author of. The introduction of Tele2 in the Dutch market did lead to the introduction of “unlimited” offers, first by T-Mobile for €35 and later by Tele2 for €25. Such offers are not common in three MNO markets. According to Rewheel, the price per GB is significantly lower in four MNO markets and the gap between three and four MNO markets is growing. Interesting are comparisons between Austria, Belgium and Germany on the one side and the Netherlands on the other side over the same period. The moment the Netherlands went from a three to four market, the prices per GB dropped and usage went up. This didn’t happen in those other countries, who have three mobile operators, to the same extent, so saying it is part of a trend and implying it is not because of competition is very odd. The effect in France in 2012 was similar with the fourth operator adding subscriptions for as low as €2 (100MB+100Min+100SMS) and €20 (for 25GB and unlimited calls). We can see similar trends in other markets with new entrants and the reverse in markets with mergers (See OECD-report)

Investment will not increase more than prices.

With regards to investment Prof. Verboven says: On the other hand, such mergers also lead to a considerable increase in the investment per operator. As a result, our findings indicate that mobile mergers do not reduce total industry investment, contrary to theoretical concerns raised by competition authorities.” This is odd because Prof. Valletti said the research doesn’t actually make those claims. The Politico article suggests that they show a trade-off between quality and price or more precise between network investment (which he uses as a proxy for quality) and price. He states that the Cerre report shows that investment grew more than the prices raised. It is however the opposite by a five to ten times.

The report states: “A hypothetical average four-to-three symmetric merger in our data would have increased the bill of end users by 16.3%, while at the same time capital expenditure would have gone up by 19.3% at the operator level, always in comparison with what would happen in the case of no merger. More realistic asymmetric four-to-three mergers (between smaller firms in European countries) are predicted to have increased the bill by about 4–7%, while increasing capital expenditure per operator by between 7.5% and 14%.” These numbers are however relative. But they are relative to different base numbers:

Dutch mobile operators had € 4.749M in retail revenue in 2017 and €167M in investment per operator (670M total). A 16.3% increase would lead to €774M more revenue. A 19.3% increase in investment per operator would lead to (670/4)x19.3%= €32M more investment per operator (€97M total). The smaller numbers are even less favorable (€356M increase in prices and €70 increase in investment). That’s nowhere near a significant rise in investment. It’s like me saying my niece got 700% older in the last week, while I aged only 0.05%. It also explains why the author’s couldn’t find an overall increase in investment in the market. Using their numbers it’s clear that in the Dutch market the fourth operator’s investment wouldn’t be fully replaced. At the same time consumers would pay over half a billion more per year… for what exactly?

There are some arguments that might explain why investment is roughly the same in a three and four operator market. One example we found in the OECD-report is that in a number of countries with four operators, there were initiatives to share some of the fixed infrastructure, such as sites, poles and sometimes even active equipment. This was less prevalent in markets with three operators. One could also imagine that third parties, such as tower companies are more active in four operator markets, leasing out locations to multiple operators. This allows costs to be shared over multiple operators and also saves CAPEX.

New operators increase quality

With regards to quality he states that “The merger will create a mobile telecom operator with a sufficient customer base to invest in a nationwide 4G and 5G network and compete effectively with the two larger fixed-mobile operators.” The arguments he gives are that it will allow the two to spread investment, particularly for 5G, over both their customers and that locations to place antenna are scarce and less competition would allow better coverage. On the Belgian market he even states that an extra operator would lead to decreased coverage of rural areas. As stated in the previous paragraph in four operator market there is often more sharing of infrastructure. Which is for example the case in the Netherlands between Tele2 and T-Mobile. This doesn’t mean that the coverage is significantly less. Indeed, coverage in the Netherlands is for all operators in the top of the world according to various metrics.

According to professor Verboven his research showed that the introduction of a fourth operator in France led to lower priced, but also lower quality offers. With regards to the situation in France, the article by Marc Bourreau prof. Verboven references states that: “We show that the incumbents’ launch of the fighting brands can be rationalized only as a breakdown of tacit collusion in product lines: before entry the incumbents can collude on suppressing low-cost brands to avoid cannibalization, and after entry this semi-collusion becomes more difficult to sustain because of increased business stealing incentives.” Though in the article low quality is mentioned a few times, it is unclear what the author’s with low quality as the incumbents use their challenger brand on their own network. It appears its more perceived quality and maybe the internet-only nature, than the actual offer.

Quality is harder to measure, as it can mean many things to many people. The experience in France is that the new operator Free increased quality in service offers by adding contracts that could be cancelled any time, free international calls (now more than 100 nations), free roaming (also in a number of nations outside the EU) and innovations in purchasing and leasing handsets, all in a fixed price offer of €20 (or €16 for fixed line customers). The competitors followed in their offers. There were complaints about coverage, however it met its coverage obligations. It also leased access on Orange’s network for increased coverage, so it’s hard to say this is a lower quality offer than the one of its competitors. For France the OECD report found also that operators pulled their investment in 4G forward by 2 years to better differentiate from Free. So for the French quality increased on many different scales.

Indeed the article states that low-cost brands aren’t necessarily lower quality as they often introduced new features that appealed to customers in various ways. The article ends with the statement that: “A general conclusion from our analysis is that concentrated market structures may facilitate tacit collusion on restricting product variety. This adds to traditional concerns that increased concentration may facilitate collusion in prices or quantities, with a potential of generating considerably larger losses to consumers and welfare.” So it is difficult to see how Prof. Verboven reaches the conclusion that in France the introduction of Free led to lower quality for consumers, or that a fourth operator in Belgium would lead to a significant impact on quality and lower investments.

Conclusion

All in all, I find it very strange that a professor of a renowned university makes claims in sponsored articles, aimed at influencing decisions by the competition authorities of the European Commission that aren’t supported by the studies referenced. In addition that the claims he makes obfuscate the relative size of effects. Yes, investment may grow a bit more in percentages, than the costs to consumers, but in Euro the last number is an order larger. His call on the Commission to apply cutting edge economic analysis, begs the question whose analysis he’s referring to as it appears his own research doesn’t support the statements he makes in this article.